Global Spillovers of Carbon Taxes: How Emissions 'Leak' to Developing Countries

Diego Känzig (Northwestern University), Julian Marenz (London Business School) & Marcel Olbert (London Business School)

In tackling climate change, the stakes are global, but the solutions often remain local, tailored to specific countries or regions. One of the key tools used, especially in Europe, is carbon pricing—taxing emissions to discourage polluting activity. Yet, while carbon taxes are effective in lowering emissions in regulated areas, they also have unintended consequences that reach far beyond national borders. A particular concern is carbon leakage, broadly defined as the shift of greenhouse gas emissions to countries with less stringent regulation. Measuring leakage is challenging, however, because of the difficulty of tracking emissions across borders (Fowlie and Reguant, 2018).

In a recent study, we present new evidence on carbon leakage, focusing on developing countries (Känzig, Marenz, and Olbert, 2024). Developing countries are attractive destinations for carbon leakage because they tend to have laxer environmental standards. Yet, developing nations have historically contributed little to climate change, which raises important equity concerns.

The Global Impact of Local Policies

Europe has been a leader in climate policy, implementing one of the world’s first large-scale carbon markets with the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), launched in 2005. This system caps emissions from high-polluting industries, requiring companies to pay for their carbon emissions—a structure intended to reduce pollution and fund the EU’s green transition. In addition, many European countries have adopted national carbon taxes, covering sectors outside the EU ETS.

In theory, this approach incentivizes firms to adopt cleaner production methods. However, it also raises the cost of operating in Europe compared to regions without similar restrictions, and may lead some firms, especially multinational corporations, to shift their emission intensive activities to other, less regulated countries.

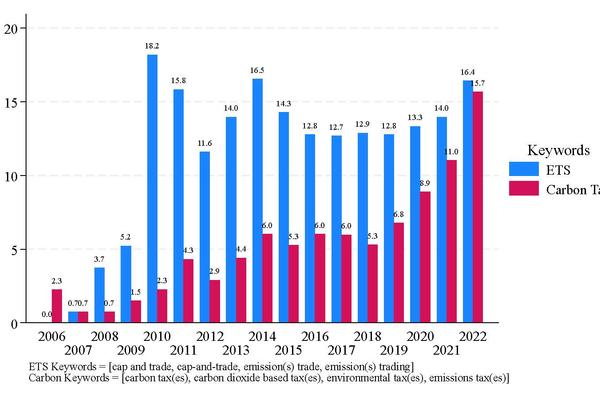

We show that multinational firms view carbon policies as a financial burden, based on a textual analysis of corporate disclosures in 10-K filings. Figure 1 illustrates an increasing trend in firms citing carbon policies as a business risk, with more than 15% of sample firms discussing these policies in 2022. This finding suggests that multinational corporations factor carbon taxes as significant costs when determining where and how to conduct business.

Figure 1: Rising Financial Materiality of Carbon Policies for Multinational Firms

Measuring Carbon Leakage from Europe to Africa

We propose a new strategy to measure carbon leakage, exploiting information on multinational firms’ exposure to carbon taxes in Europe, their subsidiary locations in Africa and geospatial emissions data. We assemble a unique dataset, mapping thousands of multinational firms’ subsidiaries in Africa alongside emission data over several years. This extensive dataset allows for a detailed examination of how companies adjust to carbon taxes by moving parts of their production to regions where carbon costs are lower or non-existent.

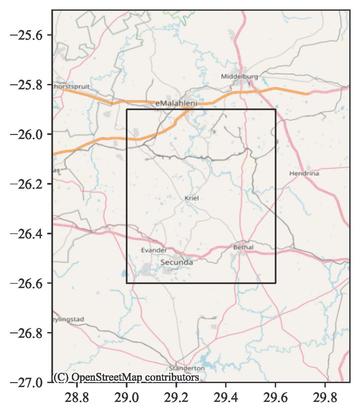

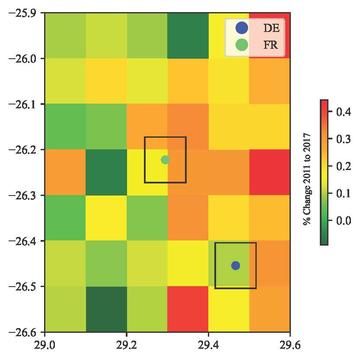

Our empirical design leverages the fact that not all multinationals are equally exposed to European carbon prices. Focusing on Africa—where many European multinationals have established subsidiaries—we find that, as domestic carbon prices increase, emissions and economic activities at African subsidiaries of more exposed multinationals rise relative to subsidiaries of less exposed multinationals. This effect is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows a differences-in-differences comparison of two subsidiaries in South Africa: one owned by a French multinational subject to a carbon tax, and the other by a German multinational without such a tax. From 2011 to 2017, the French-owned subsidiary saw a notably higher increase in emissions compared to its German counterpart, providing direct evidence of carbon leakage.

Figure 2: Carbon Leakage Example – Emissions of Subsidiaries in South Africa

(i) Zoom Area

(ii) Subsidiary C02 Emissions

Why Leakage Matters

The leakage effects we document are statistically and economically significant. At the aggregate level, an increase in the exposure to European carbon policies by one standard deviation leads to an increase in emissions in Africa of about 5 percent, While this is a non-trivial effect, the carbon leakage we estimate is unlikely to undermine domestic emission reductions in Europe, especially given that emissions in Africa are at a much lower level to start with.

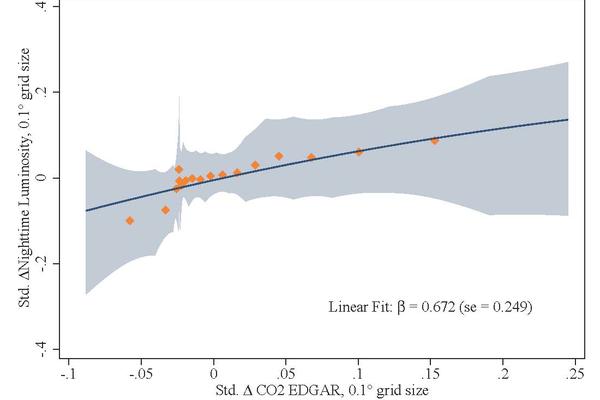

However, carbon leakage has important local impacts in Africa. When a company relocates parts of its production to developing countries, it brings economic activity, jobs, and tax revenues to those regions. Figure 3 shows a strong positive correlation (0.67) between emissions data and economic activity, proxied by nighttime luminosity, at the grid-cell level in Africa. Descriptive correlation analyses further show that luminosity aligns with rising emissions, suggesting that production shifts driven by carbon tax policies in Europe do indeed spur economic activity in less-regulated regions.

Figure 3: Link Between Economic Activity and Emissions in African Subsidiaries

Policy Implications and the Road Ahead

This highlights a critical tension between environmental protection and economic development. To address the problem of leakage, Europe is introducing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) in 2026, which aims to equalize the carbon costs for imported goods, similar to those incurred by domestic production.

However, its one-size-fits-all approach raises concerns. The current proposal makes no distinction between developing and developed economies, offering neither exemptions nor extended transition periods for lower-income countries. This uniform treatment has sparked fears, particularly among African nations, that the CBAM could impede their industrial development and economic growth trajectories (Energy Monitor, 2023).

While carbon taxes and emissions trading are effective within specific jurisdictions, they fall short as global solutions without international cooperation. Carbon leakage shows that climate policy cannot be fully effective in isolation

For policymakers, the challenge is to design strategies that prevent carbon leakage while supporting sustainable development in the least developed regions. The fight against climate change is global, and, as our study illustrates, so are its challenges.

References

Energy Monitor. (2023). How CBAM threatens Africa’s sustainable development. Retrieved November 6, 2024, from https://www.energymonitor.ai/policy/carbon-markets/how-cbam-threatens-africas-sustainable-development

Fowlie, M., & Reguant, M. (2018, May). Challenges in the measurement of leakage risk. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 108, pp. 124-129). 2014 Broadway, Suite 305, Nashville, TN 37203: American Economic Association.

Känzig, D. R., Marenz, J., & Olbert, M. (2024). Carbon Leakage to Developing Countries. Available at SSRN 4833343.