Harnessing global financial transparency to improve tax enforcement in developing countries.

Niels Johannesen (Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation)

Governments have developed a potentially powerful approach to enforcing taxes on offshore financial income and wealth: automatic information exchange across borders. In this column, and in a recent paper, the author discusses whether the approach is suitable for developing countries with limited administrative capacity and whether there exists a better alternative.

Financial secrecy in offshore financial centers like Switzerland, Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands has long facilitated tax evasion in other countries. Offshore tax evasion is associated with sizeable revenue losses (Zucman, 2014). Further, it contributes to the erosion of tax progressivity (Johannesen, 2023) as the undeclared offshore assets are heavily concentrated in the hands of the wealthiest (Alstadsæter et al., 2019; Johannesen et al, 2022).

In the past decade, governments have developed an ambitious policy approach to addressing this challenge. Under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), banks are required to identify foreign beneficial owners of financial accounts and share account details with the home countries of these account owners. Third-party reporting is known to be an effective deterrent of domestic tax evasion (Kleven et al., 2011). Hence, extending reporting requirements to foreign banks should, in principle, significantly reduce the scope for offshore tax evasion.

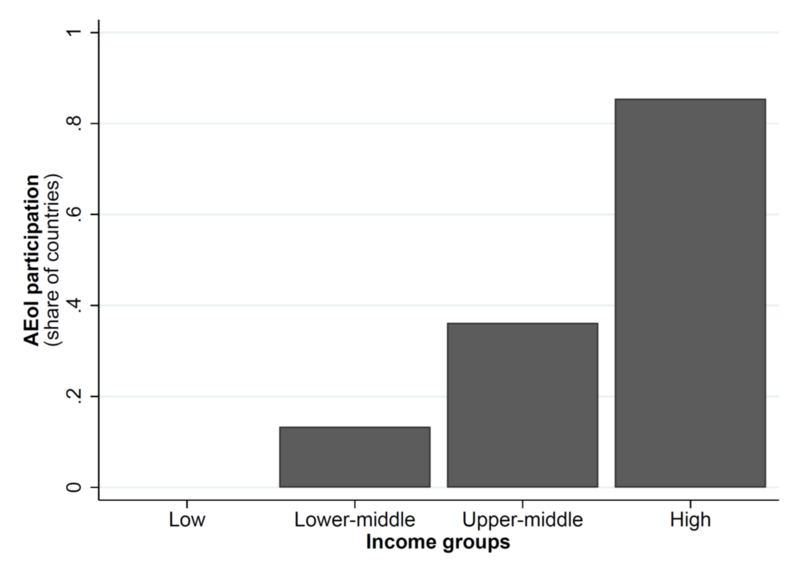

It is doubtful, however, whether the potential for improved tax enforcement will materialize in developing countries. As shown in Figure 1, only a small fraction of low-income and lower-middle income countries participates in the automatic information exchange. This may seem puzzling. Why has the overwhelming majority of developing countries opted out of a policy that promises to end offshore tax evasion?

Figure 1: AEoI participation by income level

Note: The figure shows how participation in automatic information exchange correlates with the level of economic development. Sources: Global Forum and the World Bank.

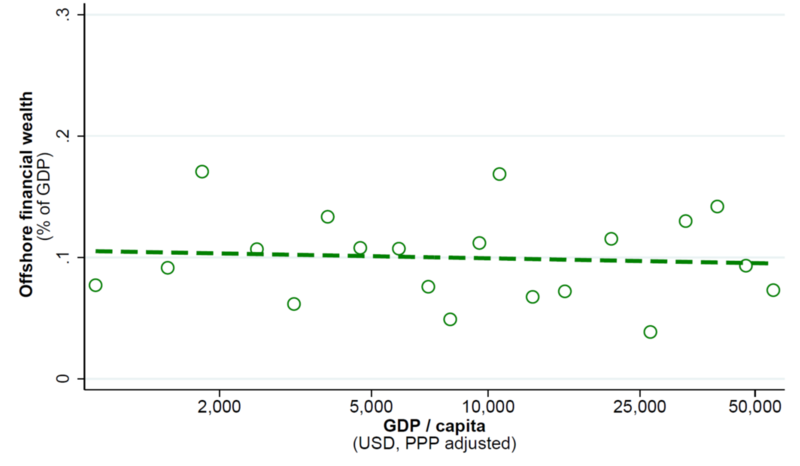

One hypothesis is that offshore tax evasion is really a rich-country phenomenon. If tax evasion through offshore tax havens causes only small revenue losses in low-income countries, it would be sensible for these countries not to participate in costly policy initiatives to reign it in. As shown in Figure 2, this hypothesis does not fit the available data. Offshore financial wealth is not systematically lower in low-income countries than in high-income countries of the same economic size.

Figure 2: Offshore financial wealth by income level

Note: The figure shows how households' financial wealth in offshore tax havens correlates with the level of economic development. Sources: Alstadsæter, Johannesen and Zucman (2018) and the World Bank

Rather, the low participation of developing countries suggests that the mode of international cooperation, with a strong emphasis on information exchange, is unattractive for countries with limited administrative capacity. Processing large datasets with information about taxpayers’ foreign accounts and using the information for tax enforcement requires significant investments. When tax authorities lack the resources to make these investments, participation in automatic information exchange may not be attractive.

Is there a way to modify the mode of international cooperation such that developing countries would be able to capitalize on the striking improvements in financial transparency achieved in the last decade?

One option would be to complement the information flows that are currently at the heart of the international cooperation with revenue flows. Under this alternative policy design, offshore banks would not just provide information to the home country of foreign account owners. They would also levy a withholding tax on the income flowing to foreign-owned accounts and remit the revenue to the home country of these account owners.

Modifying the policy in this way should not involve large additional compliance costs for banks. They are already making the costly effort to identify beneficial account owners and they are generally familiar with withholding taxes on financial income, which they are required to apply in many other settings.

Moreover, the proposed design resembles the key mechanism for ensuring taxation of offshore interest income under the EU Savings Tax Directive from 2005. It is widely believed that the EU policy was a failure, but rather because of other design features than the withholding tax mechanism (Johannesen, 2014; Martínez-Toledano and Roussille, 2023).

From the perspective of developing countries, this alternative design may be attractive because there would be a revenue gain without any commitment of scarce administrative resources. Although the withholding tax itself would arguably need to be levied at a flat rate, this would not constrain countries' policy choices with respect to the ultimate taxation of financial income. It would be possible to maintain the redistributive properties of the tax system by including foreign financial income in the tax base subject to progressive taxation while giving credit for taxes withheld by foreign banks.

This blog is based on the following paper:

Johannesen, N. (2024). Offshore tax evasion in developing countries: Evidence and policy discussion. UNU-WIDER working paper 2024-15.

REFERENCES:

Alstadsæter, A., Johannesen, N., and Zucman, G. (2019). Tax evasion and inequality. American Economic Review, 109(6), 2073-2103.

Alstadsæter, A., Johannesen, N., and Zucman, G. (2018). Who owns the wealth in tax havens? Macro evidence and implications for global inequality. Journal of Public Economics, 162, 89-100.

Johannesen, N. (2014). Tax evasion and Swiss bank deposits. Journal of Public Economics, 111, 46-62.

Johannesen, N., Reck, D., Risch, M., Slemrod, J., Guyton, J., and Langetieg, P. (2023). The Offshore World According to FATCA: New Evidence on the Foreign Wealth of US Households. NBER working paper w3105.

Johannesen, N. (2023). The end of bank secrecy: implications for redistribution and optimal taxation. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 39(3), 565-574.

Martínez-Toledano, C., and Roussille, N. (2023). Tax Evasion and the “Swiss Cheese” Regulation. Working Paper.

Zucman, G. (2014). Taxing across borders: Tracking personal wealth and corporate profits. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 121-148.