The Impact of the Minimum Wage on Independent Businesses

25 September 2024

Nirupama Rao (University of Michigan) and Max Risch (Carnegie Mellon University)

Proposals to raise the minimum wage are often met with arguments that independent businesses may be particularly vulnerable to wage floor increases (e.g., see reporting in the Wall Street Journal (2015) and Forbes (2021)). Though recent research has found that minimum wage increases have had few deleterious aggregate employment impacts in the shortrun (Cengiz et al. (2019), Dustmann et al. (2021), Dube et al. (2010), Allegretto and Reich (2018), Harasztosi and Lindner (2019)), fears that independent businesses operate on margins too slim to accommodate cost increases or face demand too elastic to pass costs through to consumers motivate small businesses exemptions and even wholesale opposition to raising wage floors.

In a recent paper, we present a comprehensive examination of how independently owned (i.e., not publicly traded) businesses accommodate minimum wage increases in the United States (Rao and Risch, 2024). To track impacts on these independent firms and their workers, we construct novel panel data by matching the universe of tax returns of U.S. independent businesses (pass-through firms) to the individual income tax returns of each of their workers and owners over a 10-year period. To estimate the impact of the minimum wage, we compare the outcomes of firms and workers in states that raise the minimum wage to similar firms and workers in states that left their minimum wages unchanged. The administrative data allow us to carefully track the various margins of response among the most exposed businesses, restaurants and retailers, including changes in their workforce, wage bill, revenues and non-labor costs, and the ultimate impact on owner profits and firm viability. Additionally, we take a worker-level perspective and track how ostensibly vulnerable populations fare following the minimum wage increases in their states.

How independent businesses accommodate minimum wage increases

First, we examine how independent businesses change their workforces following minimum wage increases and find only modest adjustments. Firms do not engage in layoffs but offer slightly fewer part-time jobs in a year. The result is about 1.5 fewer employment relationships per firm per year, driven exclusively by jobs paying less than $4,000/year, largely held by teenage workers. On average, the workforce remains largely unchanged, though a few part-time teenage jobs are no longer offered at the new higher wage level.

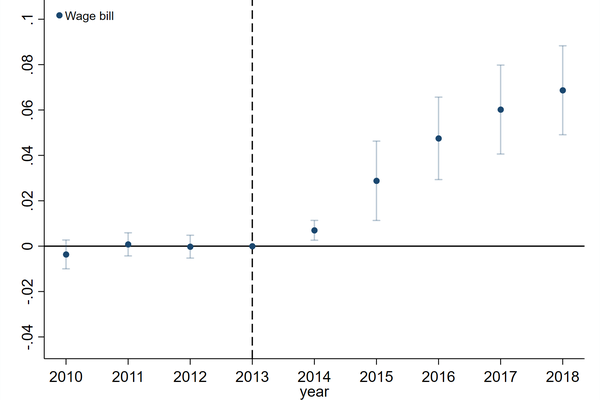

Firms do not respond with substantial labor force reductions, and, as a result, we find that firm wage bills rise by about 7% on average (Figure 1). We next investigate how small businesses finance the new higher labor costs. We find that firms are able to increase their revenues sufficiently to fully cover the new costs such that there is no reduction in profits among surviving firms on average (Figure 2). Effectively, the higher wages are fully financed by consumers rather than small business owners or by reductions in compensation for higher-earning workers.

Figure 1 - Changes in wage bill (relative to 2013)

Figure 2 - Changes in revenue (relative to 2013)

Though surviving firms can generally finance the higher wages by generating more revenues, higher minimum wages may affect the viability of businesses. We find that, in fact, the minimum wage does affect the number of small businesses operating in an exposed industry, with about 1.5% fewer businesses following the minimum wage increases. But, we find that the lost businesses are less productive on average. Only firms productive enough to earn revenue sufficient to pay workers the new higher wages survive. As a result, the minimum wage changes the composition of firms, rendering the exposed industries more productive on average. Total revenues are similar but are reallocated toward more productive firms, and workers receive a higher share of revenues as a result.

Effects on potentially vulnerable workers.

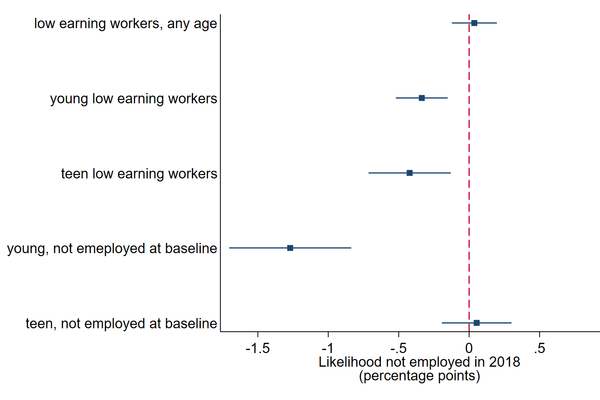

The firm-level employment analysis shows the impact of firms’ adjustment process on jobs. The lack of meaningful employment impacts suggests that higher wages lead to higher incomes for the lowest paid workers. Yet, the reduction in firms, reduced part-time hiring of teenagers and potentially different adjustments at large publicly traded businesses will also shape the income trajectories of workers.

To learn how minimum wage policies affect the earnings of the workers they are aimed to help, we construct two complementary individual-level panels. 1) A panel of low-earning workers which describes how the annual earnings and employment of typical low-wage workers are affected by minimum wage policies, but as it conditions on employment in the year prior to the policy change, cannot capture the impacts on worker entry. 2) A panel of young individuals between ages 15 and 26 who may or may not be employed prior to the minimum wage increase, which informs how the entry and earnings of those who may lose their first foothold in the workforce as firms hire fewer part-time teenagers are affected by wage floors.

Using these panels, we find that four years after a minimum wage increase:

- Low-earning workers are no less likely to be employed at some point in the year and earn about $2,000 more per year on average (Figures 3 and 4).

- Young individuals with no job prior to the minimum wage increase were more likely to be employed and earn about $2,000 more on average. The same is true for young workers who were previously employed (Figure 4).

- Retention rates rise. Workers are more likely to remain at the same employer following the minimum wage increase, potentially enhancing firm productivity and facilitating the revenue increases.

Figure 3 - Change in earnings of low-income individuals

Figure 4 - Employment probabilities

Summary

Together, the evidence shows that independent businesses are largely able to accommodate minimum wage increases without substantial workforce changes by financing higher labor costs with increased revenues. Yet, the higher wage floor affects the viability of certain small businesses such that only businesses productive enough to operate while paying the new higher wages can survive. Nonetheless, potentially vulnerable workers are no less likely to be employed in a given year following the minimum wage increase and earn significantly more per year. Taken together, the minimum wage shapes the productivity distribution businesses in the exposed market while redistributing from consumers toward workers who now receive a larger share of firm revenues.

References

Allegretto, S., and Reich, M. (2018). Are Local Minimum Wages Absorbed by Price Increases? Estimates from Internet-Based Restaurant Menus. ILR Review, 71, 35-63.

Belman, D., and Wolfson, P. J. (2014). What Does the Minimum Wage Do? Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Cengiz, D., Dube, A., Lindner, A., and Zipperer, B. (2019). The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3), 1405-1454.

Dube, A., Lester, T. W., and Reich, M. (2010). Minimum Wage Effects across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92, 945-964.

Dustmann, C., Lindner, A., Schonberg, U., Umkehrer, M., and vom Berge, P. (2021). Reallocation Effects of the Minimum Wage. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137, 267-328.

Forbes (2021). $15 Federal Minimum Wage Attacks On Small Businesses.

Harasztosi, P., and Lindner, A. (2019). Who Pays for the Minimum Wage? American Economic Review, 109, 2693-2727.

Rao, N., and Risch, M. (2024). Who’s Afraid of the Minimum Wage? Measuring the Impacts on Independent Businesses Using Matched U.S. Tax Returns. Working Paper.

Wall Street Journal (2015). As Minimum Wages Rise, Smaller Firms Get Squeezed.