Should women pay lower taxes?

We all know about the gender pay gap: the fact that men on average earn more than women. In the UK, this amounted to a 7.9 percent difference among full-time employees in April 2021, according to the Office for National Statistics. If governments are worried about the gender pay gap, why do they not simply tax men more and women less, such that they receive more equal after-tax earnings?

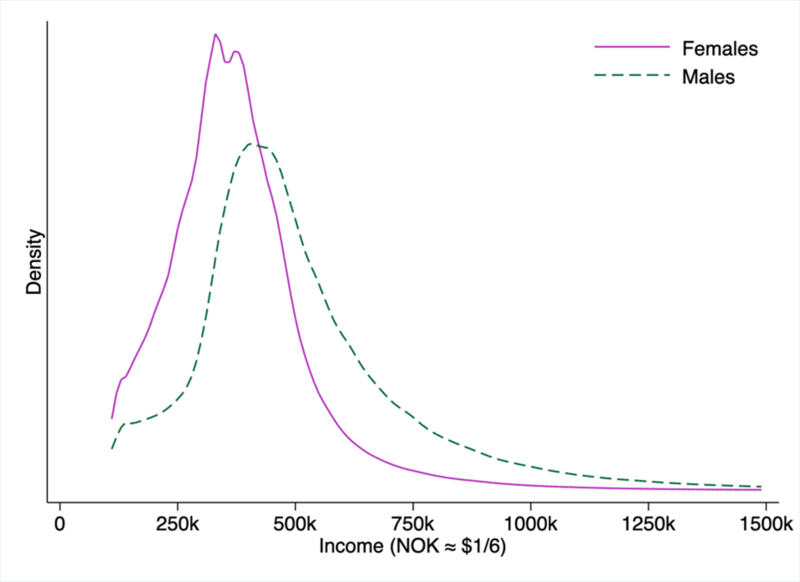

In a new working paper, I study the relationship between redistribution and non-discrimination in tax policy, with an application to a hypothetical gender tax in Norway. The paper presents two empirical findings. First, women and men have different income distributions. Figure 1 shows that women have a much more concentrated distribution at middle earning levels, while at the top of the income distribution there are mainly men.

Figure 1: Wage income distribution for females and males. Norway 2010

Second, there are gender differences in behavioural responses to taxation. If someone works less when they are taxed more, it is costly to tax them, as their behaviour is distorted by the tax. Typically, responsiveness is measured by the elasticity of taxable income, that is how people’s pre-tax earnings change due to taxation. I have estimated this elasticity for Norwegian women and men by reference to a relevant tax reform in Norway. My estimates are relatively low compared to corresponding estimates for the UK, but the focus here is that the elasticity for women is about 0.1, while it is close to 0.05 for men. This means that an increase in the marginal tax rate for women would reduce their pre-tax earnings by about twice as much as the same tax increase would for men.

The question is still why women respond differently than men do. One suggestion is that married women are more flexible in their labour supply choice. This seems not be the main explanation in Norway. My finding is that single women if anything have a slightly higher elasticity than married women. I suspect that the difference is driven mainly by labour market characteristics. More women than men work part time, and this makes it more attainable for women to adjust their labour supply when their taxes change.

In total, both the differences in income distributions and in elasticities could support the argument that women should pay lower taxes than men. One possible implementation of that approach could be to introduce a lump sum tax (fee) on men and give the proceeds to women. This would reduce both income inequality and economic distortions.

Even though these facts are well-known, we observe few countries that explicitly set lower taxes for women than men. There are often subsidies to mothers, and some countries have lower taxes for second earners (and other have higher), but few policies are based purely on the gender of the taxpayer. It is also noteworthy that even though there are many advocates for equal pay, there are few advocates for lower income taxes for women.

One reason could be that societies prefer to use other policies to combat the gender pay gap. If women are paid less than men due to discrimination, it may make more sense to address the discrimination directly rather than compensate women through the tax system. Many countries have laws against unequal pay for the same work. However, many of the reasons why women earn less than men are structural. Different occupations have different salaries, and there are more women in sectors with lower pay, such as health care. If this is hard to change, why should governments not use tax policy to compensate women for their lower pay, at least until the gender pay gap is closed?

However, we cannot conclude from this analysis that gender-based taxation is the right policy. The optimal tax policy depends not only on these economics factors, but also on values. Although economists are experts on the relevant facts, it is not clear that society wants an expert’s judgement on values. The point is that society may worry about the gender pay gap, but it may also be concerned with other fairness norms. One such norm could be non-discrimination in tax policy.

That concept has a long history in taxation under the name horizontal equity. Horizontal equity has typically meant the “equal treatment of equals”. One way of understanding this is as protection from discrimination, implying that certain characteristics, such as gender, should not be used in setting tax policy.

It is likely that many societies support such a principle. Governments sometimes protect certain characteristics, such that policy should be “blind” with respect to them. Another popular intuition is that it is fairer to be treated based on a choice rather than based on something one cannot change. More broadly, surprisingly few taxes are based on characteristics that are hard to change. This is strange to an economist, as characteristics seem like perfect bases for taxation: they are related to earnings potential and a tax on them leaves little scope for any behavioural response. Still, such taxes are contrary to common intuitions about what is right.

In conclusion, even though tax policy could address the gender pay gap, it does not follow that gender-based taxation is the optimal tax policy. Horizontal equity may provide a justification for why governments, even though they worry about the gender gap, do not set lower income taxes for women than men.